For the first time since at least 1980, I went back to revisit THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT, Nigel Kneale's teleplay published as a book by Penguin, then republished by Arrow.

Beyond, "It's brilliant," I have not much to say, but a few stray thoughts might be worth consideration.

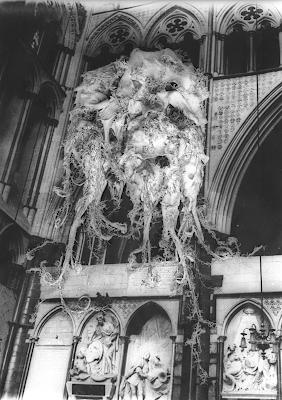

I read this long before I saw the Hammer film, which struck me as less an adaptation than a desecration. The film tossed away the most disturbing and conceptually interesting of Kneale's ideas, and turned his biological threat against all forms of life on Earth into a typically-tentacled space blob. It also rejected Kneale's ultimate solution to the teleplay's problem, but more on that later.

The film in itself might not be at fault in this. To function at his best, Kneale required time and room to develop his ideas. In shorter forms (like the stories of TOMATO CAIN, or the teleplays of BEASTS), or even in film adaptations written by Kneale himself (especially in FIVE MILLION YEARS TO EARTH), Kneale's best qualities vanished, but in THE YEAR OF THE SEX OLYMPICS, THE ROAD, and the longer Quatermass teleplays, his ideas and their implications were given space to grow, with a result of greater scope and greater tension.

For all that I admire Kneale's development of his ideas, the ending, here, has never quite convinced me. Yes, it is original and unexpected (even if it has been foreshadowed earlier in the play), but is it believable? Even after the passage of decades, I have no firm opinion. It is what it is.

In his introduction to this book, Kneale writes, "It has been pointed out that I don't really write science-fiction at all, but just use the forms of it. I suppose that's true." But is it true?

One thing is clear: Kneale has done his research. His multi-stage rocket and its re-entry process, his correct use of terms like braking ellipse, apogee, centrifugal force, show that he understands the language and basic principles of rocketry. He also understands how to go beyond ideas into their implications, which seems to me a fundamental component of any good science fiction, in print or on film. So yes, Kneale was indeed writing science fiction.

Excellent science fiction. I would call THE QUATERMASS EXPERIMENT the best alien invasion story since Wells, but Kneale would surpass EXPERIMENT six years later, with QUATERMASS AND THE PIT. That one is magnificent.